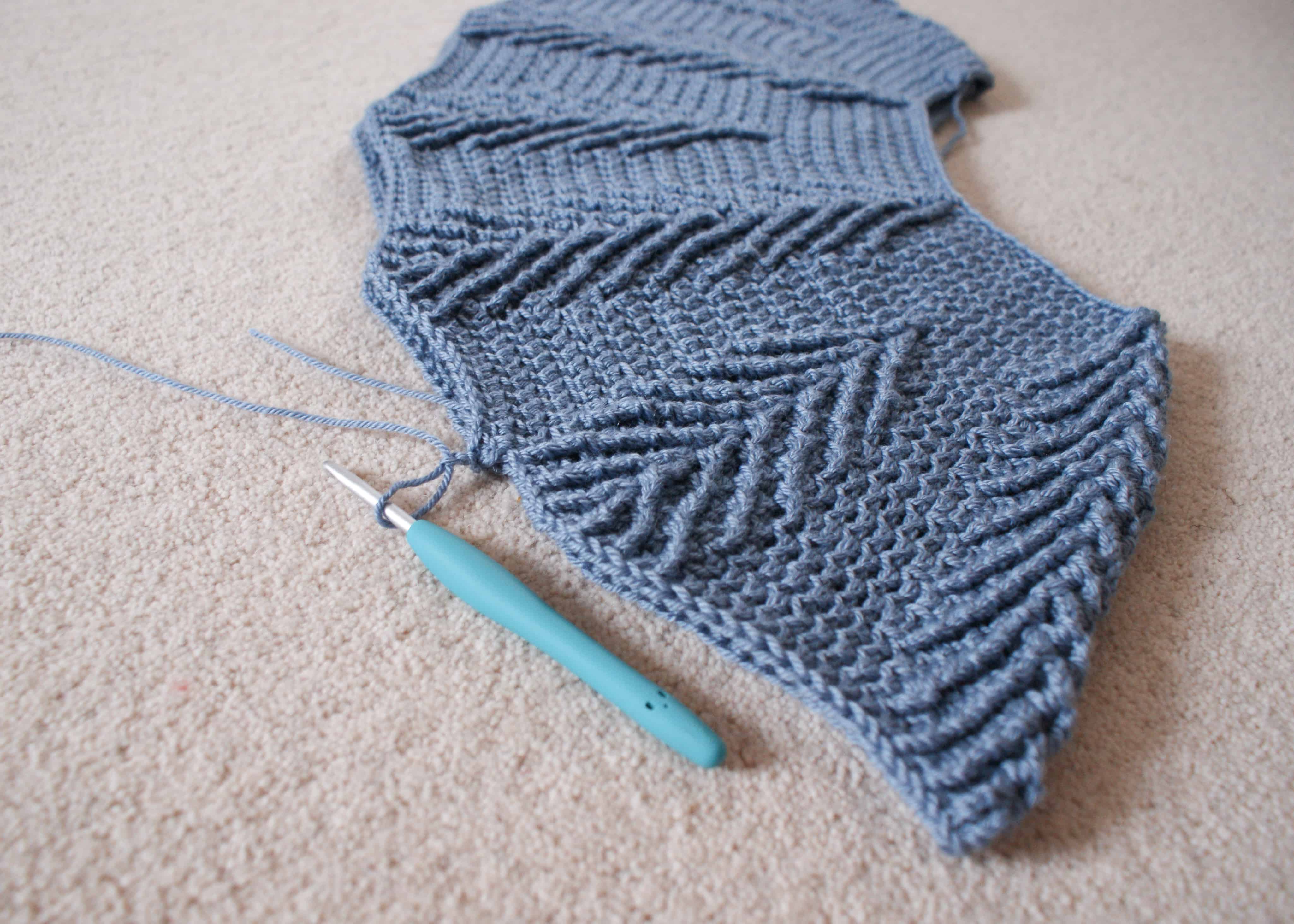

How to design a round yoke crochet sweater

When I first started designing top down crochet sweater patterns, I had no idea how to get my numbers and measurements to add up to make the thing I wanted to make.

It took a lot of scribbling and swearing to get it to work for the first few designs. Eventually, helped by the process of designing the Any Yarn Will Do Sweater, I created my own, more consistent approach.

I get a lot of people asking me where to start when it comes to designing top down garments, so I thought it might be helpful to share my approach.

There may be many other ways to approach this design process that I am not familiar with. This is the one that I have found works for me and I am sharing it from the perspective of my experience only.

Other designers may use different approaches which may be equally as effective.

Spoiler: There is no magic formula which works for all yokes.

The challenge of the crochet yoke sweater

This is a summary of the question I get asked all the time (and the crux of what a top down design needs to achieve):

“How do I know how many increases to work over how many rows to get the right yoke size?”

After a lot of research (mainly from knitting resources), swatching, frogging designing and testing, I have found a basic approach which works for me and I will outline it below.

I want to caveat that with the comment that this is always a starting point rather than a definitive “one size fits all” solution for any round yoke design.

The truth is that, whilst top-down round yoke sweaters are a dream to make (no seams, no sewing!!), I find them a real challenge to design (double that if you’re designing raglan!).

If you have found a simpler way to crunch the numbers I would LOVE to hear from you!

The math(s) you need

Although the maths isn’t quantum physics level, there is quite a lot of it involved – especially if you are grading your sweater for multiple sizes. But you need to not be afraid of it – I will explain it as clearly as I can.

My advice is to start with a single size. Get a pen and paper to scribble your numbers down, then use a spreadsheet to do the heavy lifting. (This also comes in handy when you are nudging your numbers around to get everything to fit!). If you’re not used to it, this tutorial will explain how to calculate stitch and row counts based on gauge, which is essential to getting your numbers right.

If you’re new to crochet garment design altogether, you might want to start with my design basics article: How to design a crochet sweater in 7 steps which explains my basic approach to crochet garment design.

This post focuses specifically on top down round yoke sweaters, so it is going to assume you have a basic understanding how they are constructed. If you’re new to top-down, you can read more about general top down construction here, learn my top-down tips here as well as how I advise makers to adjust top down garments in this article. All of this information is important to understand before you start designing.

If you’re interested in raglan designs, the same basic principles apply to those outlined here and I touch on the specific challenges with raglan at the end.

Okay, lets get stuck in!

How to design a crochet top-down round yoke sweater

Below I outline my approach to designing a top down round yoke sweater. I reiterate that there is no single way to approach this and this and these guidelines are based on my personal experiences and reading.

1. Decide on your stitch pattern, yarn and hook

Though it might evolve throughout the design process to accommodate the shaping, start by deciding on the main stitch pattern you are going to use.

Make sure your hook and yarn combo have a drape which will be suitable for a garment.

You’ll need to think about how your stitch pattern can be increased. This may be as simple as working 2 stitches in one but if you choose a stitch pattern which uses multiples, it will be more complex. Either way, it’s important to factor this in at the early stages.

2. Make and measure your swatch

Make and measure your swatch. If you’ve not done this before then you can read this post on how to make and measure a gauge swatch.

The calculations you will need to make will be based on an accurate gauge measurement (blocked) so there is no skipping this step. Having the unblocked measurements is also helpful so that you can check you’re on track whilst making the garment.

Note that your swatch should use the same yarn, hook and stitch pattern you are going to use in the actual garment.

If you’re turning after each round, you can make your swatch flat and turn after every row.

If you’re going to be working in rounds without turning then you will either need to make a swatch in the round too, or you can work in rows but pull a long length of yarn at the end of each row and go back and start the next row on the same side – it’s messy but it works.

This article looks at the differences in crocheting in rounds vs rows and why it’s important you swatch in precisely the same stitch pattern you’ll be working with.

The swatching process is your chance to cement your stitch pattern and note down your stitch and row multiples which are also essential to know before you start.

It’s also the time when you should confirm how your stitch pattern will be increased. Have a play and see what does and doesn’t work. You will likely change the increase distribution but it’s important to understand your options.

Write down your gauge stitch and row measurements (before and after blocking), taking note of any required pattern multiples.

3. Understand and write down your measurements

Sketch out the shape of your design and start working out what measurements you want to achieve.

You’ll need to know the collar, chest, bicep, and armhole depth measurements to start with.

I normally start working on my numbers for one size then do the maths for all the other sizes to check it is scaleable.

You’ll need to know the following measurements for your design:

- Circumference at Neckline

- Circumference of Yoke at Split (which includes chest and sleeves)

- Depth of Yoke before Split – Distance from neckline to underarm

There are no set numbers for these measurements as they depend on the design style. The Ysolda measurements charts do have a yoke guidance but I do not use these.

The sizing you choose will depend how much ease you want for each area (i.e. how much bigger than the body the sweater will be, particularly at the chest and underarms). Start with some approximate numbers and you can adjust to suit as you do the maths.

How do I know how big to make the neckline?

I use the Craft yarn council standards to base my measurements on. However, they do not have a section on collar size – I’ve found this one of the trickiest measurements to get right. I normally work somewhere between 45-70cm circumference, depending on the size and neckline style I’m working with.

I (personally) prefer to go larger if I’m worried about fit because I hate tight necks and I know I can always adjust on the collar later! That said, crochet sweaters tend to stretch so you don’t want it too big either.

The beauty of top down is…. yes… you can try it on as you go. And with the neckline there is very little frogging if you need to change it after 2 rounds!

How do I know how big the yoke should be when I split it?

This is the formula I use:

[(Bust + Ease) – (2 x underarm chain)] + 2 x[(Bicep + Ease) – underarm chain]

The ease you add to the bicep and bust will be part of your design decision. I usually add a much smaller amount of ease at the bicep than the bust because I like fitted sleeves in round yoke sweaters.

The length of the underarm chain is another design decision. This area is a great place to build in flexibility. The length of the underarm chain is not set. According to the Elizabeth Zimmerman method, the underarm chains should be 8% of the bust measurement, but this should be seen as an approximate starting point and not an absolute.

How deep / long should my yoke be?

This is dependant on the neckline size and stitch pattern. It can be a tricky one to get right. I use the armhole depth measurement plus a few cm ease as a starting point for this.

If your yoke is too long then it could kind of trap the arms by the sides, so every time you lift up your arms, it may do weird things on the shoulders.

Too short and your garment will be too tight at the underarm.

Can I use proportions or percentages to decide on my yoke measurements?

There is some guidance in knitting resources that offer a proportionate approach to creating yokes. This offers each measurement as a percentage of the bust.

There seems to be variation in the proportions depending on which resource you use, so it is important to know that this is only a rough guideline.

The style and shape you want your sweater to be will dictate your measurements first and foremost. For example if you want a wide neckline or oversized sleeves, the percentages below will not be correct.

I first found this guidance offered by knitting stalwart Elisabeth Zimmerman but some other designers have created their own versions of this guidance which works for them. below is a summary of the proportionate approach.

- Neckline = 40% of bust

- Underarm chain = 8% of bust

- Bicep = 30-40% of bust

- Cuff = 20-25% of bust

Again, I emphases that these are just a rough guide and should be taken with a pinch of salt. We are all different shapes, sizes and proportions so the best way to get measurements if you’re designing a sweater for yourself is to use your own measurements.

Furthermore, it’s important to remember that, although similar crochet is not the same as knitting, which these percentages were developed for, and that crochet fabric can behave differently.

For me, the underarm chain guidance is probably the most useful piece of data.

Where to short rows come in?

You may have seen many discussions about using short rows in round yoke designs. These are used in order to stop the garment rising up at the back. To raise the back neckline essentially.

Short rows are usually either added right at the start of the yoke, so you’re working with an oval / asymmetric circle (is that a thing?) rather than a round head hole.

Alternatively they can be added once you are ready to split the yoke, to create more coverage low-down. This always felt counterintuitive to me because I would think you need more fabric over the bust at the front, but it seems to work consistently for those who use it (which I have not done), so I bow to other’s experience here.

None of my round yoke designs contain short rows as part of the pattern, though I experimented with adding them to the neckline retrospectively during the Any Yarn Will Do CAl, so do check that out if you want to explore further. I liked working with short rows at the neckline so it’s on my list for the next round yoke garment I design.

4. Crunch the yoke numbers

Take your measurements (which you have written down or plugged into your spreadsheet) and use these with your stitch and row gauge to calculate the following:

- Number of stitches at neckline

- Number of stitches at yoke split (including how many will be allocated to the body and sleeves)

- Number of rows from neckline to yoke split

This post explains how to calculate your stitch and row counts based on your gauge.

Once you have these numbers, you can adjust them to meet your stitch and row multiples. You’ll need to make sure that these multiples work for the body and sleeves.

Calculating your increases

Next, need to work hot how many stitches you’ll need to increase by from the neckline to the end of the yoke. To do this, you will deduct the number of neckline stitches from the number of stitches at the yoke split.

As you also have the number of rows you have to make those increases over, you can get started on working out how to place those increases.

This is where it gets tricky!

This post explains how to calculate how to evenly distribute increases and decreases, however, this is on a row by row basis. It’s not a magic formula for the maths you’ll need to do here, but may give you a starting point.

I don’t have a formula for placing these increases but these are the tips I’ve learned after many many false starts:

- Think about how a simple flat circle increases and try to mimic that approach.

- It’s important to have non-increase rows between the increase rows in a round yoke.

- Changing the cadence of your increases throughout the yoke can create different shapes around the shoulders – there is a lot of discussion about placing most of the increases right near the start of the yoke but I have yet to quantify this.

- If you place too few increases on increase rows you’ll end up with a square / rectangle (so you’re basically working a raglan) or pentagon or hexagon etc., which can get bumpy and look ugly when you go to to split the yoke.

- Too few increase points can also make the increases pretty obvious in the finished sweater, especially if the increases are stacked – you may want to think about using invisible increases (described in my amigurumi tips post).

- I personally aim for a minimum of about 10 stitch increase on your increase rows, though the more increases you have, the more circular your yoke will be – to some extent this will also depend on the yarn weight you’re using

- Some knitting resources recommend only having 4 or 5 increase rows over the course of the entire yoke – this is more akin to the pi circle method and can be a useful approach, especially if you are including colourwork in your yoke

- The cadence of increases will differ with different sizes – I normally find that when grading I use one cadence for for XS-XL and then need a different approach for 1-5XL.

- Plug your numbers into a spreadsheet and play with changing things up until you’re happy with the distribution of your increases

Ultimately, the decision about how to place and distribute your increases from neckline to yoke is the designers prerogative. Whilst there are wrong ways to do this, there isn’t a single right way. It’s an individual choice only you can make.

The top part of the corona vest had only 6 increase points and, as you see, it’s quite hexagonal. However, as this is just the collar part, and the body uses increases more often it works. You can change your increase distribution up to match the style of top you’re making.

Getting this right is the biggest challenge when it comes to this design process. It’s the part where a lot of designers give up. It’s hard. I’m not going to pretend otherwise!

Once you have decided on your chosen cadence for the stitch increase and a set of numbers you’re happy with, then get going.

If you’re not sure if it will work then give it a try anyway. My advice is always to experiment, so try out several different approaches as messing it up and refining is my favourite way to learn.

I can tell you that it took me a LOT of trial and error to get this right – even with working my numbers out in advance – so if it doesn’t go right first time, don’t be discouraged. With each iteration you will learn.

The maths in top down round yoke sweaters is dependent on so many variables which is why there’s no simple formula. Just go for it until you get a feel for what works. Some times there is just no substitute for experience.

What about splitting the yoke?

When you split the yoke, you’ll need to know the answers to the following (for each size):

- How many stitches do I need for the body

- How many stitches do I need for each sleeve

- How many chains do I place at the underarm

You can simply calculate the first two from your original set of numbers (again, adjusting for stitch multiples), so you just skip the number of stitches for the sleeve when splitting the yoke.

You may want to consider here where you want your joining seam to be. Some people like it at the back and some like to hide it at the underarm / side seam. If you’re working in continual rounds then you won’t have a seam at all.

Underarm chains are important to allow movement, but the length of these will also be dependant on the ease you are working with. The knitting proportion mentioned earlier suggests 8% of the bust, but this is another designers choice only you can make.

Once you have successfully split your yoke and are happy with the fit, the rest is child’s play (in relative terms at least). Just work your body and sleeves with the appropriate shaping and you are away.

I have a separate article about sleeve shaping which you might find useful, but if you’ve mastered the yoke increase then I expect you’ll be fine with the rest!

The challenge with grading yoke garments

This post wouldn’t be complete if I didn’t touch on grading. This, for me is where one of the biggest challenges lie. If you’re designing a round yoke garment for yourself then you only have one set of measurements you need to satisfy. The cadence of your increases just need to work for you. This is why I think this is a great place to start.

However, when it comes to grading the pattern to fit multiple sizes, you have a whole set of measurements which those stitch increases need to work for.

Body proportions to not increase with increasing size in a linear way. So just because the bust increases by 2 inches, it doesn’t mean the armhole depth or bicep measurement increase at the same rate.

THIS is why there is no magic formula.

It’s also why, in many yoke patterns, you will see a section of the yoke instruction split out into separate sizes. Because you will almost always need to customise the pattern to meet the specific proportions of that size.

In the any yarn will do sweater, for example, I tackled this by using different increase multiples for different sizes. Working with circles gives you a lot of freedom in this regard.

With something simple, like a drop shoulder sweater, you can just add stitches to the width of the body panel to change the bust size, then change the depth of the side seam to accommodate the armhole. With a yoke, you have to allow for these changes both at once… in 3D…

I don’t tell you this to put you off attempting to grade a yoke. I just want to help you understand the things you need to consider.

It is totally achievable. It’s just a lot!

How to design top down raglan yokes

So far, this post has focused on round yoke designs. Generally speaking, the same principles apply when designing a top down raglan garment. However, in my experience Raglans are more complex to design in multiple sizes.

The main additional challenge with raglan designs is that you typically only have 4 points at which to place your increases. And these increases impact the size of both the bust and the sleeves. This adds restrictions when you are working out how to space your increases once you’ve done the sizing maths.

Having just created the Any Yarn Will Do Cardigan pattern, which uses a Raglan yoke, I feel like this restriction in the increases can be a blessing and a curse. The limitation of 4 increase points gives you less options to choose from, in terms of how you space the increase, but can mean you have to make adjustments elsewhere, such as at the neckline.

The approach to top down yoke design is definitely a balancing act. It’s super challenging but incredibly satisfying when you finally get the numbers to bend to your will!

If you’re new to working with round yoke designs, I hope that you find this helpful.

I’m really passionate about demystifying the crochet garment design process, so if you have any questions or tips that work for you then I would love your input. Just pop a comment below or reach out on my socials – I could chat about this stuff all day!

Happy Designing!!

Dx

Copyright Dora Does Limited, Registered in England, Company Number 13992263. This pattern is for personal use only and may not be shared or reproduced in written, photo, video or any other form without prior written consent. All rights reserved. Terms of service.

My problem with round yokes is that, well, they are round. A standard neckline is flatter at the back nd lower in the front. How can we make a ‘’round” neckline that mimics this?

Adjusting the neckline on a round yoke is usually done by adding short rows at the beginning of the yoke to create an asymmetric shape around the neckline. I talk about this in my any yarn will do sweater call (week 6 I think) and I demonstrate how I approach this method of customising.